Criminalizing aggressive war

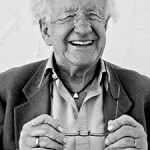

By Johan Galtung

Kuala Lumpur, February 24, 2014

Few, if anybody, today argue this so forcefully as Mahathir Mohammad, Malaysia’s fourth prime minister, for 22 years. He compares what we do when one person kills another to all we do not do when millions kill millions in aggressive wars. We have clear laws, we apprehend the suspect, weigh the evidence for or against in court, and, if found guilty, the murderer is punished. There may even be a system of compensation for the bereaved.

But in wars among states the murderers get medals and honors, and if victorious relish a post-glory exuberance disorder, nourishing a new aggression. And the bereaved are left with their grief and a post trauma stress disorder, nourishing the idea of revenge. Madness, irrationality, a social evil of top rank, to be abolished. As Mahathir says: “Peace for us simply means the absence of war. We must never be deflected from this simple objective”. An important reminder for all who broaden the concepts of violence and peace: remember the essence!

One approach is criminalization. For that clear laws are needed, meaning without loopholes. The UN Charter is an effort (Articles 1.1 and 2.4) prohibiting war and the threat of war among (member) states. The two explicit exceptions are the use of force by the UN Security Council, and the use of force for individual or collective defense (articles 42 and 51). Libraries have been written about this.

However, when people feel they have legitimate human rights that are left unattended, in the end they may resort to violence. A key example in today’s world is the case of non-dominant nations: most, say, 174 UN member states are multi-national but only 4 have managed equality among the nations: Switzerland and Belgium in Europe, India (not in Assam) and Malaysia in Asia. With an average of 10 nations per state with one dominant nation – and the diplomats work in the interests of that one – there are potentially 1,500 wars. We have had and have some.

The obvious solution is to learn from those four: a federation inside the state with equal levels of autonomy for the nations, and a community, a confederation with neighbors as the nations often cross those borders. However, diplomats tend not to work for that but for the dominant nations, and the UN is also a trade union of governments preferring unitary states. The road ahead passes through theory and practice of conflict resolution. Thus, in an octagonal world like:

India China

Russia OIC

USA EU

Latin America Africa

(“USA” also covers Israel and Japan; ASEAN-Association of Southeast Asian Nations is between China and OIC-Organization of Islamic Cooperation)

There are 28 bilateral relations replete with potentials for conflict and cooperation. A major task is to identify conciliation for the traumas of the past, solutions for the conflicts of the present and constructive ideas for the cooperation of the future.

As professor Liu Cheng of Nanjing University points out in an upcoming major book on peace studies: in a world with so many shared values and so much interaction, wars simply do not belong. And wars become even more absurd – a total disconnect between values and facts, culture and structure – against a background of what can be done.

And here the past comes to our assistance. We have not managed to abolish war – in fact, major wars threaten – but we have had much success with two other major social evils, slavery and colonialism, and humanity is working on two others, patriarchy and eco-crisis. There are things to be learnt about success and failure from all four, as good hypotheses for a possible carry-over to abolition of war through criminalization.

Mahathir actually sees war as a lack of civilization, and it certainly is, for any reasonable interpretation of being civilized.

But how about terrorism? They are already criminalized. What is not criminalized is state terrorism, killing so many more, maybe 99:1. There is an International Criminal Court – except for the USA.

And that brings us from a focus on the geography of the present world and the historiography of the past world, from alternatives to war and what we can learn from struggles against other social evils, to the criminalization itself. We are talking about a legal approach in a broad sense. In that approach, ius cogens – seen as compelling law – plays a key role in the protection of human life against crimes like torture and genocide.

But even more die from starvation, yet that is not recognized as such, possibly because it may be due more to acts of omission than to acts of commission. Aggressive wars, however, mandated by the UN Security Council or not, attempted justified as defensive wars or not, are clearly acts of commission. That there are problems of definition and of drawing borders is clear. There is a process making the space for “legitimate, necessary war” smaller and smaller; the question is how to speed up the process.

One approach would be through the universalization of law, making all crimes against humanity punishable everywhere. Wars of aggression presuppose decisions at the top of states, making their acts of commission potentially punishable in any country. The Pinochet case comes to mind, and the important role of the former Spanish judge Balthazar Garzón. There are ambiguities, and possibilities all over.

Three approaches have been indicated on the road to Mahathir’s vision of a civilized world: geographical, historical and juridical, as the research part of the Mahathir Chair for Global Peace Studies – GPS for short – at IIUM, the International Islamic University of Malaysia.

As the first holder of the chair – two years from 1 March – I am deeply honored and challenged by this opportunity to dedicate teaching and research to this lofty goal and welcome all possible ideas and advice.

This article was originally published at Transcend Media Service here.