The Unlikely AMEXIT: Pivoting away from the Middle East

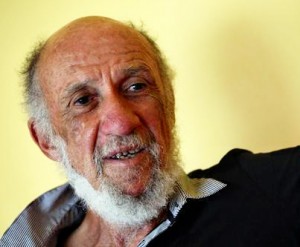

By Richard Falk

The Case for Disengagement

A few years ago Barack Obama made much of an American pivot to East Asia, a recognition of China’s emergence and regional assertiveness, and the related claim that the American role in Asia-Pacific should be treated as a prime strategic interest that China needed to be made to respect.

The shift also involved the recognition by Obama that the United States had become overly and unsuccessfully engaged in Middle Eastern politics creating incentives to adjust foreign policy priorities. The 2012 pivot was an overdue correction of the neocon approach to the region during the presidency of George W. Bush that reached its climax with the disastrous 2003 intervention in Iraq, which continues to cause negative reverberations throughout the region.

It was then that the idiocy of ‘democracy promotion’ gave an idealistic edge to America’s military intervention and the delusion prospect of the occupiers receiving a warm welcome from the Iraqi people hit a stone wall of unanticipated resistance.

In retrospect, it seems evident that despite the much publicized ‘pivot’ the United States has not disengaged from the Middle East. Its policies are tied as ever to Israel, and its fully engaged in the military campaigns taking place in Syria and against DAESH.

In a recent article in The National Interest, Mohammed Ayoob, proposes a gradual American disengagement from the region. He makes a highly intelligent and informed strategic interest argument based on Israel’s military superiority, the reduced Western dependence on Gulf oil, and the nuclear agreement with Iran.

In effect, Ayoob convincingly contends that circumstances no longer justify a major American engagement in the region, and that to maintain the commitment at present levels adds to Middle East turmoil, and its extra-regional terrorist spillover, in ways that harms American interests.

Why Disengagement Won’t Happen

Ayoob’s reasoning is flawless, but disengagement won’t happen, and not because Americans are not smart enough to recognize changed circumstances. The pivot to East Asia was a recent instance of such an adjustment based on an assessment of changed geopolitical circumstances. Actually, the high degree of American involvement in the Middle East was itself the result of an adjustment to changed circumstances.

After the Soviet collapse, the earlier geopolitical preoccupation with Europe seemed superfluous and outmoded, and the Middle East with its oil, Israel, expanding Islamic influence, risky nuclear proliferation potential seemed then like a region where a strong American commitment would solidify its role as global leader.

This perception was reinforced after the Al Qaeda 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon, which gave neocon hawks a pretext for a regime-changing attack on Iraq, which the neocons hoped was but a prelude to a more elaborate political reconfiguring of the region by way of regime-changing interventions.

The Iraqi undertaking failed miserably during the state-rebuilding occupation that followed upon the attack and overthrow of the Saddam Hussein regime. The master plan involved reconstructing the government and economy of Iraq to serve Western interests while at the same time supposedly democratizing the country. It totally backfired.

This American pivot to the Middle East after the Cold War was based on the geopolitical opportunism of Washington in a context of a persisting failure to understand the changing circumstances of the post-colonial world, and especially the altered balance between the military superiority associated with foreign intervention and the resourcefulness of territorial resistance.

So why the inflexibility with respect to the Middle East when disengagement brings immediate major practical advantages? Part of the explanation is surely governmental inertia, reinforced by the belief that the changes in conditions are not as clear and favorable as Ayoob contends, making disengagement seem geopolitically vulnerable to future charges that the Obama presidency was responsible for ‘losing the Middle East,’ as if it was ever America’s to lose!

More to the point is a range of other reasons militating against disengagement.

Perhaps, most significant, is the militarist bias of American foreign policy that is even unable to acknowledge that the attacks on Iraq or Libya were failures. This refusal to think outside the military box prevails in American policy circles, making the debate on what to do about Syria or DAESH center on the single question of how much American military power should be deployed to resolve these conflicts.

What Eisenhower called the military industrial complex has come to dominate the machinery of government in Washington, further abetted by the accretion of a huge homeland security bureaucracy since 9/11. Real threats to American interests exist in the Middle East, and given this unwillingness to rely on political or diplomatic solutions for the resolution of most disputes, virtually requires the United States to retain its military presence to ensure the availability of options to intervene militarily whenever the occasion arises.

Then there is the anti-international mood that has taken over American domestic politics. It is hostile to every kind of international commitment other than military action against real and imagined Islamic enemies.

Additionally, the US Congress has been completely captured by the Israeli Lobby, which puts a high premium on maintaining the American geopolitical engagement so as to share with Israel the burdens and risks associated with the management of regional turbulence. As neither the Arab uprisings of 2011 nor the robust counterrevolutionary aftermath were anticipated, it is argued that there is too uncertainty to risk any further disengagement.

This is coupled with the claim that the rapid drawdown of American combat forces in Iraq was actually premature, and led to a resurgence of civil strife that has persuaded the Obama administration to redeploy American troops both to aid in the fight to regain territory occupied by ISIS and to help the government to establish some degree of stability.

Why Disengagement Should Happen

Neither realist arguments about interests nor ethical considerations of principle will lead to an overdue American disengagement. Washington refuses to understand why intervention by Western military forces in the post-colonial Middle East generates dangerous extremist forms of resistance (e.g. DAESH) magnifying the problems that prompted intervention in the first place. In essence, the intervention option is a lose/lose proposition, but without it American engagement makes no sense.

Unfortunately, for America and the peoples throughout the Middle East the US seems incapable of extricating itself from yet another geopolitical quagmire that is partly responsible for generating extra-regional terrorism of the sort that has afflicted Europe in the last two years.

And so although disengagement is a sensible course of action, it won’t happen for a long, long time, if at all.

Unlike BREXIT, for AMEXIT, and geopolitics generally, there are no referenda offered the citizenry.