Why Congress should say “NO” on Syria

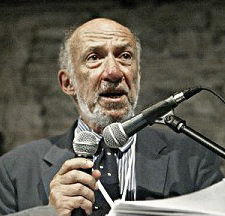

By Richard Falk

I am not sure this attempt at clarifying the present stage of the Syria debate adds much to my prior posts, yet I hope that it provides a kind of summary that is helpful in following the unfolding debate; all along I have felt that the Syrian impasse presented the UN and the world with a tragic predicament: trapped between doing something to stop the Assad regime from committing atrocities against its own people so as to retain power and the non-viability and illegality of military intervention, a predicament further complicated by the proxy war within the region along sectarian lines, by the strategic involvement of the U.S. and Russia on opposite sides, and the maneuverings behind the scenes by Israel; also, the overall regional turmoil, and past bad feeling in relation to the UN role in the overthrow of Qadaffi posed additional obstacles.

Efforts to shape the political outcome by military means, because of the proxy war dimensions (including an increasingly evident, although still surprising, tacit alliance between Israel and Saudi Arabia) only escalated the violence on the ground in Syria; Turkey, Russia, and the United States have all along oscillated between principled and pragmatic responses favoring one side or the other, and exhibiting an ambivalent commitment to equi-distant diplomacy.

There are three positions that have considerable support in Washington circles, although rarely acknowledged and not popular with the public, partly because of recent foreign policy failures, and partly too removed from perceptions of genuine security interests:

– undertake an attack to uphold ‘red line’ credibility of the president and the United States Government;

– undertake an attack to avoid an insurgent defeat, but on a scale that will not produce an insurgent victory; goal: keep the civil war going;

– undertake an attack to convince Iran that Obama is ready to use force if diplomatic coercion doesn’t work.

There are several other considerations that need to be taken into account:

– the Assad regime is guilty of numerous crimes against humanity aside from and prior to its probable (although far from assured) responsibility for the August 21st attack with chemical weapons on Ghouta; Syria lacks a legitimate government from the perspective of international criminal law; with respect to the violation of the Geneva Accord with respect to chemical weapons, the responsibility of Assad personally and the Syrian government generally has not been established beyond a reasonable doubt at this point;

– nevertheless, the Assad regime retains considerable support from various segments of the Syrian population, possesses substantial military capabilities, and is unlikely to collapse without a major ground invasion; the Assad government retains a measure of legitimacy from the perspective of the politics of self-determination;

– insurgent forces are divided, without coherent leadership, and are also responsible for committing atrocities, and contain political extremists in their ranks; a victory by the insurgency does not seem likely to lead to legitimate governing process from the perspective of law and morality;

– the negative American experiences of relying on war in Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan should create a presumption against the authorization of force and reliance on military option in conflict situations; there is mounting evidence from past cases that the costs and risks associated with military options tend to be grossly understated during pre-war debates in the United States due partly to the political mobilization role played by mainstream media;

– the diplomatic alternative to military force has been handicapped by its past abuse in the UN Security Council with respect to Libya authorization of ‘responsibility to protect’ undermining the trust of Russia, China, and others, and by the refusal to bring Iran into the political conversation as a key actor.

Against this background there are four important independent reasons for Congress to withhold authorization in this instance:

1) a use of force that can neither be justified as self-defense, nor is authorized by the UN, is contrary to the UN Charter, which is an obligatory treaty, as well as being the most serious type of violation of international law in a post-Nuremburg world; the Nuremberg precedent with regard to crimes against peace (as the ‘crime of crimes’) should be respected, especially by the United States, which continues to serve for better and worse, as the main normative architect of world order;

2) the Kosovo precedent of ‘illegal, but legitimate’ is not applicable as a military attack is not likely to achieve either its political goals of ending the civil war and of causing the collapse of the Assad regime, nor its moral goals of stopping the slaughter and displacement of the Syrian people, and the devastation of their cities and country;

3) even if the political and moral goals could be achieved, Congress, as well as the president, lacks the authority to authorized foreign policy uses of force that are incompatible with the UN Charter and international law;

4) Congress should defer to domestic and world public opinion that clearly is opposed to a proposed military attack in the absence of an exceptional demonstration can be made as to the positive political and moral benefits of such an attack; for reasons mentioned, no such demonstration can be made in this instance; even the European Union has withheld support for a military attack on Syria at the September meeting of the G-20 in St. Petersburg; only France among America’s traditional allies supported Obama’s insistence on reliance on a punitive military strike, supposedly for the sake of enforcing international law, bizarre reasoning because the rationale reduces to the following proposition: in view of the political realities, it is necessary to violate international law so as to be able to enforce it.