Police mediation: And idea whose time has come

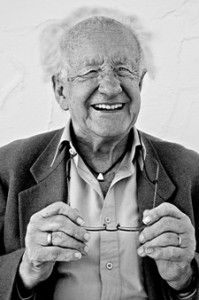

By Johan Galtung

The state system emerged in the 17th century, with institutions for force. One was for internal and one for external use: the national police and the national military, national standing for the dominant nation in the states. The role of the police was to protect elites against theft and violence by the people; crimes by the law. And the role of the military was to protect the states against each other. Both police and military occasionally initiated violence.

The description just given still holds very well for the USA. “Banking scandals” give us insight in class-conscious “justice”. Police patrol the streets, not the boardrooms. And no arrests.

But wars between states are now dwindling. They yield to wars between dominant and other nations within states, and dominant and other civilizations in the world; using state and non-state terrorism.

How did “modern” elites get these ideas? From intellectuals.

They picked Thucydides who told them that wars there will always be, and von Clausewitz who trivialized them, from Hobbes who told them that people are born violent and have to be controlled, and Machiavelli who told them that the prince has to be feared, not loved.

Or they decided themselves and picked intellectuals to confirm.

The military had an agenda: fight for victory, unconditional surrender of the other side, dictate the terms; call it peace.

The police had an agenda: detect, arrest, court, confession, sentence, punishment; call it justice. Theory: individual and general prevention, punishment not to do it again and as a warning to others.

All false, all nonsense. And wars and crimes are still with us.

But why do we have diplomacy and mediation between states but only recently alternatives to the police agenda? Brutal and simple answer: because there is not enough crime. The level is tolerable. Al Capone was needed for mediation to enter, with some mutual loss and benefit.

The first time I heard about police mediation was in Japan.

Each bloc has a police box, for patrols and arrest, and for mediation. A street brawl, a loud quarrel upstairs: they are brought to the mediation room and served tea, with very experienced older police officers mediating.

The second time was on the Malabar Coast of India.

The police was sick and tired of arresting, arraigning etc., and then re-arresting the same persons after their release from prison, ready for new crimes. They started large-scale mediation to bring them straight from (petty) crimes back to society, and apparently with positive results.

This new police agenda is now boldly advocated in the important work done in the Valencia region in Spain. The region, not known for the crimes of the small but for the economic and political crimes of the big: massive corruption, and political scandals.

The road to less crime passes through depriving crime of its class character. Spain is doing better than the USA: the big are punished. Just like the road to abolish war passes through depriving wars of their class character, condoning wars by big (veto) powers, not by the small.

There is a mediation road for police inspired by experiences with school mediation. The basic idea is the distinction between ends and means.

What we discovered was that pupils, from kindergarten onwards, often had acceptable, if not very conscious, goals. However, the means were unacceptable. So we designed the question to the bully, boy or girl, “what you just did is completely unacceptable, but why did you do it?” A question highly recommended for crimes. Mediation starts inside.

Children are not born with adequate and acceptable means-ends chains. They have to be taught, and make mistakes.

People who end up in prison are often not among the brightest–proven by the fact that they are caught – or they are on the wrong side of the class divides.

So, why do we have theft and violence; to focus again on those two crime categories? Criminology works on that, in principle.

A range of answers: from the need to feed the family to the urge for celebrity, the fame as infamous even if only for a day or two. The urge to be noted, even as notorious. To make the headlines.

Media negativism, focused on the bad, on wars and crimes, play a role; like in promoting wars. Denying them the headlines might help.

The search for something exciting, risky, to prove themselves, to outsmart the police. And the class war aspect: stealing from “them”, violence against “them” high up, as revenge for what they do to “us”, to “teach them a lesson”, should in no way be underestimated.

Alternatives?

No doubt, sports play a major role for fame, both individual and team sports. So does democracy as a nonviolent way of promoting political agendas: as political work. So does nonviolent resistance to the crimes of the elites.

And so does war, substituting one bad for the other, making the lower classes fight and die for the elites. And so did a major answer in the West: elites and people cooperating, benefiting from violence and theft from other peoples; in slavery, colonialism, imperialism, robbery capitalism. The net result is infinitely worse than crimes.

Can the police really do this job of contacting criminals, also potential criminals? The police also have the role of protection, they know whence the crime come; can go to the source.

Nevertheless, they obviously have to be well trained and paid for this new and difficult aspect of their job. Talking with them, what do you want, what are you after? Indicating alternative means, facilitating.

As good mediators would try with such big belligerents as Taliban, Al Qaeda, State Department, Pentagon, now also France, Russia and ISIS; all of them still hoping for their own violence to “teach them a lesson”.

May police mediation take roots and blossom. For more peaceful societies. For peace in general.

Originally published by Transcend Media Service here.